- Home

- Horatio Morpurgo

The Paradoxal Compass Page 3

The Paradoxal Compass Read online

Page 3

This unscheduled stop-over made, then, for an ideal opportunity to impress upon the minds of his crew the purpose of their voyage and what would be expected of them. Its purpose was to ‘discover’, i.e. find and then map, a passage to India and China through the ‘Straits of Annian’, the legendary North West Passage. Early cartographers had assumed this must extend around the top of what is now Canada. Once discovered – and its existence was an article of quasi-mystical faith at this time – the strait would open up a trade route to the Far East which would cut out the Spanish. Hence the need for secrecy.

For such a technical rehearsal these islands, in blustery weather and choppy seas, with all those tricky shallows and numberless rocks, were ideal. And their selection was not as random as it might look. The islanders themselves would have been well aware that their home was the natural testing-ground for the latest defence-related technologies.

This last English outcrop before the Atlantic was contested territory. Three years later the Armada would sail with orders to rendez-vous off the Scillies, but was blown off course before most of its ships could reach them. Their uncertain status is surely there also in the way the islands were spelt. In addition to the way we spell them now they were at this date either given their French name, Sorlinges, or had to put up whatever Elizabethan spelling felt like that day: Scylla, Cillie, Sillie, and, yes, even plain Silly. They do not appear at all, under any name, on Saxton’s great atlas of England and Wales, published in 1579.

Davis of all people, at this of all times, would have been aware of that omission and of the need to include the islands now. In June 1585 the whole country was in the grip of one of those xenophobic convulsions which we now call security alerts. The Spanish siege of Antwerp continued. The Catholic party in France was in the ascendant. And now English merchant ships had been seized and impounded by Spanish port authorities. Some response there must be. One day after Davis had left Dartmouth, Francis Drake sailed up the Thames to organise and take command of a punitive expedition involving more than thirty ships. That autumn he would embark upon one of his most disgraceful orgies of destructive violence.

That same June, Richard Grenville was leading a fleet up the coast of Virginia in search of a location for the first English settlement in North America. Indeed, the name ‘Virginia’ had been dreamed up only a few months earlier. Grenville burnt down an Indian village as he went, in reprisal for the theft of a silver cup. Spanish spies had anxiously reported his departure from Plymouth in April, unable to determine his journey’s purpose. Another fleet had been sent to raid Spanish shipping around Newfoundland in the same month. They returned with hundreds of prisoners and several thousand tonnes of dried fish.

For all of its modest scale and technical sophistication, Davis’ expedition, too, was part of this national project to ‘annoy’ the world’s only superpower. His accidental ‘discovery’ of the Scilly Isles might appear harmless enough, and indeed, by comparison it was. But even such early forays into the new science are shadowed by their consequences. A week after leaving Tresco, ‘a very great Whale’ was recorded, ‘and every day we saw whales continually.’ Ten days later they were still seeing ‘great store of Whales.’ Four centuries later, the use of that term ‘store’ comes with its own twinge of presentiment.

For there exists a perspective now, a background awareness of everything that followed, against which the ‘Age of Discovery’ appears much diminished, even fundamentally questionable. A new impermanence, seeping into our lives through everything we thought we knew, reaches out not only around the world but back across the centuries. It is impossible to miss the multiple ironies in those explorer accounts.

Davis and his men heard the other side of the Atlantic before they saw it. Three weeks after leaving Scilly, the ships ‘fell into a great whirling and brustling of a tyde’ before they entered ‘a very calme Sea’, in which they could hear, nevertheless, ‘a mighty great roaring.’

This, they assumed, must be waves breaking on a shore but the air was ‘so foggie and full of thicke mist’ that the two ships could not even see each other let alone what was further ahead. The ship’s boat was now lowered again and soundings taken, but the lead which had found ten fathoms off New Grimsby ‘could not find ground in 300 fathoms’ here.

The two ships proceeded carefully, each firing a musket into the fog every thirty minutes, to let the other know where it was. Weird forms began to loom: they ‘met many Ilands of yce floting’, midsummer pack-ice streaming south from Greenland. Davis sent men to explore these ‘islands’, which was when they realised that ‘all the roaring which we heard, was caused onely by the rowling of this yce together.’ They returned to the ships ‘laden with ice, which made very good fresh water’, the first they had taken on board since Tresco. It was only next day that the fog lifted, allowing them to see land.

From a granite archipelago, they passed over to another, of ice. So the stories we have lived by acquire a new fragility. In the following year, West Country merchants funded yet another search for the North West Passage. In a location which had been open sea a year before, Davis encountered ‘a most mighty and strange quantity of yce, so bigge that we knew not the limits thereof.’ He took it to be a new country, even sending his boat to ‘discover’ it. This vast and mysterious object, in other words, came within a whisker of being mapped and claimed for Her Majesty. The boat’s crew soon returned. It was ‘onely yce’, they reported. But the news ‘bred great admiration to us all.’ It took them nearly two weeks to sail around it. The quantity of ice, Davis wrote, was ‘incredible to be reported … and therefore I omit to speake any further thereof’. To see the New World, as others before him had already found, was at the same time to reach the limits of language.

Ancient geographers were little help in these newly discovered regions. It is difficult for us, who perhaps glance past images of the Arctic most days, to grasp now how perplexing that scenery encountered for the first time must have been. Davis gives some hints of this in that phrase ‘incredible to be reported’. One ancient explorer, a Greek called Pytheas, did claim to have travelled so far north that there was no land or sea or air but a substance which comprised all of these, ‘holding them in suspension.’ Pytheas called this substance ‘sea-lungs’. Stay-at-home scholars, listening to the explorers, assumed that their ‘Mowntaynes of Ise, somme of a myle long; somme longer’, must be what the Greeks had meant by ‘sea-lungs’.

But we are, also, in our way, at a point now where none of the categories that have served in the past help us to describe what we now see. Hence our collective difficulty in seeing it at all. Greenland welcoming the Sunneshine of London and the Mooneshine of Dartmouth with the growl of its pack-ice is loaded, for us, with ominous meaning which will have eluded Davis entirely. An ice-berg that takes two weeks to sail around, which can be mistaken for a country, can only have been part of an ice-shelf.

We too are without words adequate for what this ‘quantity of yce’ portends. We know, as Davis could not, that the Scillies, as he mapped them and as they still appear today, are a drowned landscape, the hilltops of a much larger island, submerged as sea-levels rose during the later Middle Ages. Tresco, from which he set sail, had been, a century or two earlier, part of a ‘St Nicholas’ Island’, joined by a land bridge with what is now the neighbouring island of Bryher.

A copy of John Davis’ map has survived. You can still see how the weather that June confined his ship’s boat to the more sheltered waters. The mapping of areas exposed to the west is much thinner in detail. The Western Rocks, for example, stretching from Bryher all the way to the horizon – a notorious maritime graveyard – appear as pebbles tidied into absurd little heaps. The depth at their farthest limit is marked as 18 fathoms, as if to show that they did, in spite of everything, make it that far.

The map may suggest something else, too, about those twelve days. The only features to be marked with place names in both English and Cornish are the islands of Tresco and

Bryher. Indeed the Cornish versions appear above the English ones and are in bold: Trystraw and Bryadk. They cannot have spent the better part of two weeks there without speaking to anyone. Is this concession to local sensibilities all the trace that remains of their communication?

These days any day-tripper to Hugh Town can grab a better map than this off the counter at Tourist Information. It does not, by our standards, correspond very closely to what is actually there. Some of the islands seem a bit squashed and those cartoon Western Rocks are no danger to anybody.

But it is no wonder that Davis kept quiet about what he was up to here. He was, after all, seeing this farthest corner of England as it had never been ‘seen’ before. This was a fateful moment. He took this corner of his home country and treated it as a set of points, to be triangulated like any other such set, anywhere in the world. If there was a new exactitude here, there was a new detachment, too.

A DRAKEAN ACT HAS CONSEQUENCES

The sharp drop in temperature as the new school term approached was excellent news. The blizzard they were forecasting would soon block every possible exit. And so it did. For several days I stayed on at home, enjoying an indefinitely extended Christmas holiday. I photographed the astonishing forms of the snow-drifts which had filled our lane. Even from the pages of an old album they still seem to glow with something of the gratitude I felt towards them. School was on the far side of the moor and the moor for now was impassable.

But a friend of my parents worked for the Forestry Commission and had access to a Land Rover. One greeny-grey morning, I was finally persuaded to climb into its freezing cab and watch my knees turn white as we rattled manfully along the treacherous roads. Changing schools as often as I did at that age – this was my third new one in four years – functioned like a kind of school in itself. Not a bad one, I might add. At an early age I got to meet lots of interesting people, albeit never for very long.

Several of the teachers at this latest place, for example, had come ‘home’ from Kenya after independence. One of them, formerly a farmer in the Rift Valley, taught us English literature and the Old Testament. The Rift Valley was home to the original humans, he heretically informed us, the true Garden of Eden. Its climate was the one we evolved in, which is why it still feels so perfect. He brought in books all about it to show us.

The New Testament was taught by HPW, another exile from the same East African Garden. He had no gift for classroom teaching and a rotten temper with it. But he did have a bird-table outside the window of his office and instead of telling us about the New Testament, invited us in one afternoon to watch it with him. The next week he took an interested group of boys bird-watching in the school grounds. Then he took groups of us out on a little boat he kept moored on the Tavy.

It was old-fashioned in other ways, too. It was quickly clear my parents had opted for a bracing conservatism this time around. Plymouth was close by and the dormitories were all named after naval heroes. Borough and Davis were not among them. The shoulder patches on our Navy-blue jerseys were intentionally martial-looking and the prefects wore little badges with anchors on them. The school took its maritime connections seriously. Our sports teams were feared.

Such an atmosphere was not so very strange for Devon in the late Seventies. There was a Cold War on as well as a run of bad winters. NATO and the Warsaw Pact played war games in the North Atlantic, Devonport prospered mightily and we dressed the part. Most of the boys were being paid for by the Ministry of Defence. Somebody’s father came to teach us about the Russian Navy, how to tell a Victor Class submarine from an Alpha Class one. Another father landed his green helicopter on a games field one afternoon.

Drake’s Prayer was read at Remembrance Day services and books about him were handed out as school prizes. I still have mine. Most of us were from nearby and it was expected, I suppose, that we identify with the Age of Discovery, with the disproportionate role played in it by ships based in the Western Ports.

To one suggestible eleven-year-old the offer of being inscribed in such a pedigree was attractive. HPW’s boat was moored just above Plymouth. He had, it was rumoured, ‘requisitioned’ it in northern Germany at the end of the war and sailed it home. I’m afraid I approved of this Drakean act, though it is, sadly, now too late to ask whether it actually happened. Wherever he got it from, we helped him re-launch it in the spring, just a few miles from the abbey Drake bought with the proceeds of his Famous Voyage.

We explored the thickly wooded labyrinth of waterways and tidal creeks that reach into the countryside behind Plymouth. To geographers this is a ‘drowned valley system’, submerged at the end of the last ice age. When I later came across that ‘nook-shotten isle’ phrase in Shakespeare it was immediately those outings I thought of. Some experiences turn into memory by an incremental process – sedimentary or metamorphic rather than igneous memories. Those long afternoons, tidal waters obeying their own slow laws around us, were my earliest intimation of this.

But on one trip we sailed right down into Plymouth Sound, past the rusting steel cliffs of a decommissioned aircraft carrier, past the nuclear submarine pens and finally past ‘Drake’s Island’, encrusted with mouldering air defence batteries. This, our teacher explained, was where the greatest explorer of them all had paused as he sailed into his home port at the end of the circumnavigation, with no idea what he was coming ‘home’ to.

With hindsight, there was more than a touch of the displaced person about HPW. I wonder what he really made of the country he’d come ‘home’ to. Perhaps that’s how he successfully instilled so much affection for particular places. He would take a group to the Scillies in the spring holidays and we always seemed to get lucky with the weather. It was on one of those trips that I first saw Bryher for myself. You can easily walk round it in a day. The weather was so good that even the character-building spam with which he insisted on filling our sandwiches seemed almost edible. A young merlin, my first, skimmed the heather or wheeled overhead as we made our circuit, winding up the charm.

Bryher is, to the west, open to everything the elements have to throw at it. There are bare rocks and uninhabited islands all the way to the horizon. The other way faces on to white sandy lagoons and the sheltered moorings of Tresco Channel. I still have a photograph I took that first day, of the daffodils out on my enchanted island. There is New Grimsby behind them, just across the water.

This place was everything I already loved about the Scillies from earlier trips, but in concentrated form. You admire quite indiscriminately at that age. You think the sheltered moorings and those jagged rocks out there are, somehow or other, going to complement each other. It will all add up one day. Such confidence doesn’t last and perhaps that’s just as well. Drake embarking with a fleet that will torch three cities, Grenville burning down an Indian village, Davis patiently ‘discovering’ the Isles of Scilly – at twelve you just ‘love history’, or you ‘love the Tudors’, or you ‘love Bryher’, or something like that. You’ve no idea what you’re getting into.

Sunshine or Moonshine? Drake or Davis? Paradisal lagoon one way, shipping hazard the other. Bryher was a good place to start learning how to hold both sides of a question before the mind’s eye. Connected to the world by ocean currents and the migratory routes of birds, it still retains, for me, something of that twelve-year-old’s anticipation of life. I couldn’t wait to tell my parents all about it.

Drake once sailed from Florida to the Scillies in just twenty-three days, heading home from a raid on the ‘silver train’. This was the route by which the Spanish transported bullion, on mules, from Panama City across the isthmus to Nombre de Dios. From there it was loaded on to ships for transport across the Atlantic. It was during this raid in 1573 that Drake caught his first glimpse of the Pacific. The sighting, by all accounts, struck him with a revelatory power. He was coming home now, at speed, but he knew what he had to do next.

He had with him, on that return journey, Diego, a Cimaroon. The Cimaroons were escaped slav

es who had established their own settlements in remote forests. Nobody knew the terrain better and Drake formed an alliance with them which alarmed the Spanish colonial authorities. Diego sued to be taken on board in 1573 and would sail with Drake on later expeditions, on the same terms and for the same pay as English crew. The Scillies would have been his first sight of England. With the outline of their low hills, with the white sand and glittering waters between them, he must have thought his new home was going to be a bit like the Caribbean.

At the end of my last term there, the leavers were all taken on an outing to Drake’s home at Buckland Abbey. My diary tells me he casually walked into the Great Hall as I lingered to admire the portraits: ‘I had an amazing feeling … Francis Drake walked in. I could imagine everything.’ It’s a pretty bare mention, considering. You’d think I might have recorded some part of what he said at least. Did I not have any questions? I remembered the atmosphere and the portraits in that hall but I’d clean forgotten, until I was looking through that diary years later, that he put in a personal appearance.

His reputation has risen, has fallen, has shapeshifted down the centuries and continues to do so. But that habits of veneration can be transmitted in this way, such that a schoolboy four hundred years later was still picking up residual traces of the cult, is surely passing strange.

Or possibly not. We were more haunted by that ghost ship then than we are today. Only a decade earlier, the Golden Hinde was as common as the half-pennies on which it still figured. Not only was its silhouette Devon’s county emblem but a silver model of the ship, revolving on a turntable to the sound of trumpets, preceded any programme made by local independent TV. This channel even made an interesting film about the circumnavigation, called ‘Drake’s Venture’, just before losing its franchise in 1980.

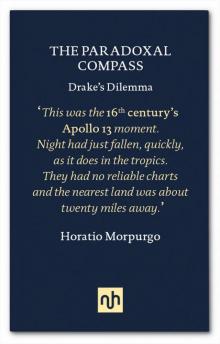

The Paradoxal Compass

The Paradoxal Compass